The Trump Economy

The goal for this piece is to be comprehensive about the effects of Trump policies on the economy. That sounds rather ordinary, but in fact most discussions of the Trump economy has been myopic to the point of misrepresentation. There are several reasons for that:

- To understand the effect of Trump’s policies you need to untangle Trump’s results from the inherited economy. People tend to shy away from that, but there is actually no alternative — otherwise there is no way to say where we are going from here. As we’ve noted before, Trump has pulled a fast one on the American public. It’s not just a matter of claiming responsibility for successes of an inherited economy. It’s that he is substituting wildly dangerous policies for the ones that actually got us here. When we last discussed that subject we could only talk theoretically, but now there is considerably more to say.

- The usual statistics (even the unemployment rate) tell you more about the business view of the world than about what it means for people. The difference between the two says a lot about the real significance of Trump policies.

- Finally, most discussions of Trump’s policies focus on results from the hugely expensive tax cuts that were done last December. However, it is at least as important to understand what we have NOT DONE because of Trump’s economic priorities. As we’ll see those sins of omission are a serious part of the picture.

The discussion plays out as a series of charts.

- Effects of Trump’s policies on the economy

We begin by teasing out the effects of Trump’s own policies from what was inherited.

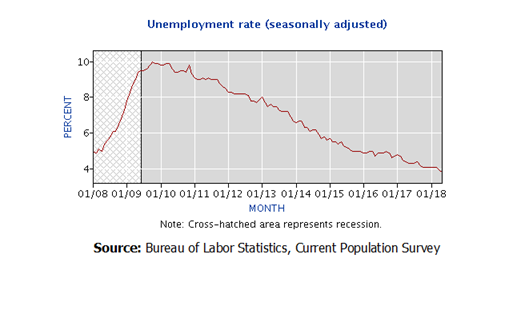

Our first chart shows the changes in unemployment rate over the past ten years:

What is most striking about this picture is the continuity: the trend line is almost straight extending through the present. That isn’t surprising. Changes in employment don’t happen overnight, and after the election there were no substantive changes in economic policy until the new tax plan was passed in December of 2017. (Reduced regulation at the EPA was never a factor, since — despite the propaganda — environment regulation was positive for jobs.)

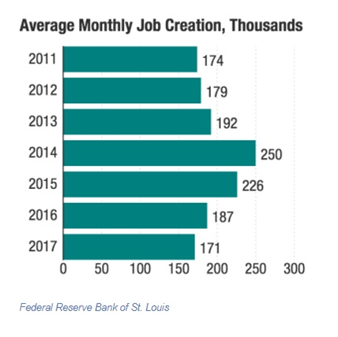

Another way of looking at the same trend is with job creation, which we see in the second chart:

Again what is striking is continuity with the inherited trends.

For 2018, however, we’re no longer in a world where nothing had changed — Congress has just passed a tax plan with monumental business tax cuts sold to the public for effects on employment and wages. Mitch McConnell was hardly shy in his comments: “Under the policies of this unified Republican government, American workers, families, and business owners are achieving economic growth that is unmatched in recent memory.”

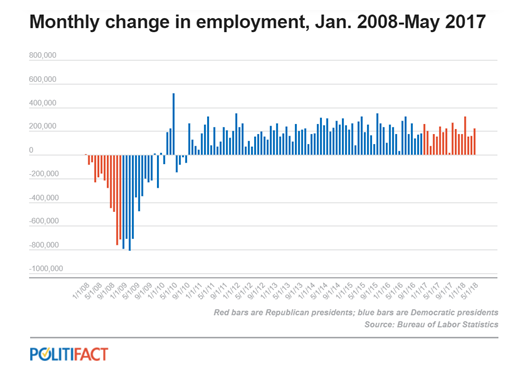

Polifact, however, examined the detailed jobs data — which looks like this:

Their conclusion was what you can see: “Since 2010 — the year the Great Recession began to wane and the recovery began — every January-to-May period saw an average monthly job gain of between 160,000 and 236,000. The performance for 2018 was slightly higher than the average, but pretty typical.”

For now, we’re not going to pronounce on whether the tax cuts will ultimately prove useful or not. However what we have seen is that even the monumental tax cuts of December, 2017 were not enough to change the clear, multi-year trend shown by all three figures. The decline in unemployment is NOT where to look for effects of Trump’s economic policy.

Where should we be looking?

To start with we need to look at indicators that are more immediately sensitive to economic changes than the labor market is. The obvious one is the stock market.

The following chart shows what has been happening to the Dow.

Starting with Trump’s election the Dow has been rising in anticipation of some form of tax cuts. Not only were those promised in the campaign, but they were the explicitly-stated objective of the major Republican donors. Corporate tax cuts, which eventually formed the biggest single part of the story, influence the market directly by going to the corporate bottom lines. (The markets correctly assumed that any payout to workers would be negligible.)

The markets continued to rise until Trump’s up and down trade wars entered the picture. Since then neither the market nor anyone else knows exactly where things are going. There are actually two negatives. First is the obvious uncertainty. Second is the fact that Trump’s specific tariffs don’t instill confidence, because they don’t match the business needs or even promote employment.

The graph above shows the uncertainty, but it should be pointed out that the performance is actually worse than it appears. The fact is that the single biggest use for the corporate tax cuts of 2017 was stock buybacks, nominally to raise share value for investors. Despite all that extra money, there is no current evidence of a solid increasing market trend. Business confidence has been replaced by nervousness. Even the Koch brothers and the conservatives in Congress are worried about the consequences of the threatened trade wars.

Then there is the matter of the deficit. With the Trump tax cuts we have undertaken massive deficit-funded stimulation of an economy at essentially full employment. Many economists at the time noted the risk of a speculative crash with nothing left to fund recovery. Recent data has underlined that risk.

In April the IMF issued a warning. They see a buildup of worldwide debt to record levels with the Chinese and the US as primary actors. This first chart shows the overall numbers; the “emerging economy” portion represents largely Chinese debt.

The next two charts show the US contribution. The first shows that the US is an anomaly among developing nations in deciding to run the risk of large deficits in good times.

The next slide adjusts the width of the vertical bar by the size of the national economy, which makes the impact of the US behavior very clear.

The overall message here is that the amount of debt makes the world’s economic system increasingly fragile. Further it should be remembered that in the 2008 crash the US and China were the major players who prevented a depression by stimulus spending. They will be hard-pressed to do it again. Just to be clear, this is not an argument about international responsibilities. It is an argument about the risk to us.

As to what would provoke such a crash, we have an obvious candidate in Trump’s trade wars. However the risks are not necessarily so exotic. Business cycles end (ten years is a long time for one), and they end just when things seem to be going so swimmingly that people get giddy — like Mitch McConnell in the quote given earlier or the many critics of Dodd-Frank. The following chart (which we’ll revisit in a minute for other reasons) shows when the past few recessions occurred.

On that basis you have to say that 4% unemployment can be dangerous territory (particularly after a multi-year stock market boom). We are quite literally going in blind with no backup. And you can be sure that if we have a problem there will be scant sympathy from an administration that hates “losers”.

- Trump’s policies and the workforce

The cheers for the Trump economy have been based mostly on the unemployment numbers. However, the chart just presented shows that is only part of the story. As is evident from the chart, each of the previous business cycles was accompanied by wage growth in recovery. But you can see that for the current cycle that wage growth hasn’t occurred. (From this morning’s NY Times: “The rise in consumer prices over the last year has effectively wiped out any wage increases for nonsupervisory workers.”)

Otherwise stated, the benefits of the recovery have most emphatically NOT trickled down to existing workers. Even in “Trump country” most people were not unemployed — the problem was replacing good union jobs with Walmart. That hasn’t gotten better.

The reasons for lack of wage growth have been much studied. The primary factors are

- Globalization

- Rise of Non-Standard Employment

- Rise of Non-Compete Agreements

- Automation

- De-unionization

All of these items reduce the power of workers in dealing with management. We won’t go through the items in detail (the referenced article does an excellent job), but the bottom line is that the Trump administration is actively engaged in making this problem worse. The anti-globalization trade wars have been of little value for workers, and on non-compete agreements and de-unionization the administration has aggressively taken the side of management against workers.

Overall the current state of the Trump economy is NOT good for workers. (It’s worth citing some additional recent data here.)

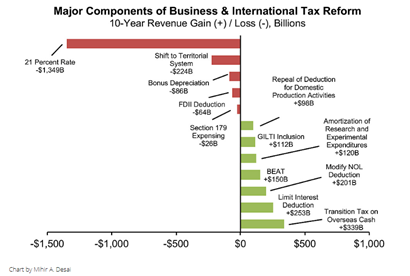

The final topic is what has not been done because of the priorities established by Trump’s economic policies. The point of departure is the following figure showing a breakdown of the financial impact of the business tax plan.

The most obvious element on the chart is the loss of income due to the corporate tax cut, alone estimated to cost $1,349 B over ten years. Since the decrease is from 35% to 21%, we get a nice round number for the effect — $100 B for each percentage point. Note that this occurred as business was doing well, the economy was close to full employment, and the actual corporate tax rate (all benefits included) was a competitive 24%, (and real tax reform could have been close to revenue neutral). Further we now know that the main beneficiaries thus far have been investors seeing results of corporate stock buybacks.

What could that money have bought?

Two obvious target areas are

- Education, where school financing has never recovered from the 2008 crash, state budget cuts have teachers out on strike, and increased public college costs have led to a generation trapped in debt.

- Infrastructure, a problem area identified by both candidates for President but unaddressed in the budget, because there was just no money left.

Estimates are available online for many projects in both areas, so with a hypothetical set of projects we can make the answer concrete:

- The estimated backlog for repairs of existing highways is $430 B.

- The estimated cost of upgrading US airports over ten years is $48 B.

- Ten years of K-12 school repair to upgrade fair and poor facilities nationwide is $380 B.

- Ten years’ worth of the estimated cost of a federal program to provide free tuition to all the US public colleges and universities is $470 B.

With $1,349 B we could have done all of that.

We can now summarize the state of the Trump economy.

- The declines in unemployment associated with recovery from the 2008 crash have continued in the same way through the Trump Presidency. No policy act of the Trump administration, including even the 2017 tax cuts, has produced a significant impact on that trend.

- Trump’s own policies have been disruptive. His repeated and ever-changing threats of trade wars have unsettled markets and businesses. Even more importantly he has embarked on massive deficit-based stimulation in good times, contributing to an IMF-identified risk of repeating 2008 or worse.

- The decline in unemployment has not produced the usual accompanying increase in wages. Some of the reasons are structural, but the Trump administration has exacerbated this effect by systematically attacking labor’s leverage in dealing with management. Despite the decline in unemployment, the Trump economy has not been good for the existing workforce.

- Trump’s tax cuts have essentially stifled any action to address the pressing problems of education and infrastructure in this country. We have become in effect a poorer country.

Originally published at ontheoutside.blog on June 12, 2018.